CLTC has announced the winners of our inaugural Cybersecurity Arts Contest. Following a juried review of proposals, six different projects were selected based on their potential to illuminate the human impacts of security and provoke critical dialogue about important issues like privacy, surveillance, cyberattacks, and malware.

The Cybersecurity Arts Contest is part of CLTC’s mission to help individuals and organizations address tomorrow’s information security challenges and amplify the upside of the digital revolution. “Artists are a critical voice for expanding the ways that the public engages with and imagines cybersecurity,” said Ann Cleaveland, Executive Director of CLTC. “We are thrilled to be able to fund these original projects in multiple different media.”

The Cybersecurity Arts Contest was launched as part of the Daylight Security Research Lab, a new initiative that aims to shift how people understand and identify the harms of technology. Artists from around the world submitted proposals that were reviewed by an interdisciplinary committee and judged for artistic merit, relevance, feasibility, and potential impact, including how they might influence other artists or reach particular audiences. The selected artists will receive funding in amounts ranging from $5,000 to $25,000, and CLTC will work with the artists to showcase their works.

The Cybersecurity Arts Contest was launched as part of the Daylight Security Research Lab, a new initiative that aims to shift how people understand and identify the harms of technology. Artists from around the world submitted proposals that were reviewed by an interdisciplinary committee and judged for artistic merit, relevance, feasibility, and potential impact, including how they might influence other artists or reach particular audiences. The selected artists will receive funding in amounts ranging from $5,000 to $25,000, and CLTC will work with the artists to showcase their works.

“Contemporary tropes of security’s representation — like the ‘hacker in the hoodie’ or the ‘scrolling green code’ — fail to capture the gravity, impact, and reach of security in daily life,” explains Nick Merrill, director of the Daylight Security Research Lab. “Through their critical and creative approaches to issues like security and privacy, these artistic works can help provoke thought and dialogue about cybersecurity.”

Below are summaries of the six Cybersecurity Arts Contest winners.

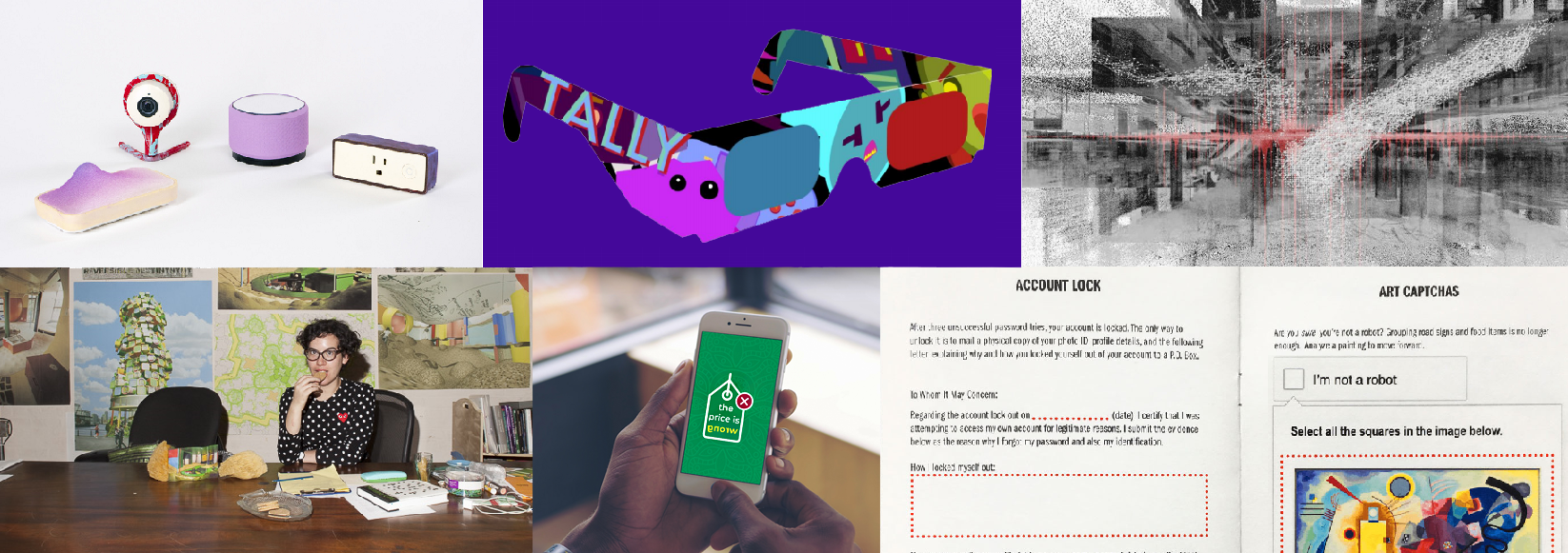

between systems and selves

Caroline Sinders

Inspired by the work of Alexander Calder and Giorgia Lupi, Caroline Sinders will develop a series of “poetic sculptures” based on malware, or malicious software, software programs that are harmful to users’ computers. Entitled “between systems and selves,” the sculptures will be designed based on different elements that are common to all malware. For example, the specific operating system a piece of malware is designed to attack will determine the shape and color of a particular sculptural element.

“The current iteration of the project is analyzing different malware viruses against a series of parameters,” Sinders explains.”These parameters are then translated into structures that will make up the sculpture. These ‘structures’ are the data points that will be visualized and in comparison to one other.”

Sinders envisions that the sculptures could exist as mobiles, hanging from a ceiling. “The output is creating, depending upon how the sculptures will be built, between 100-1,000 small physical sculptures, either made out of thin wood or metal,” she explained.

The aim is “to make malware and algorithms human readable,” Sinders says. “So much of code plays with literal human words, but uses technical processes that are hard to describe. An algorithm can do things, but why it does things is based in the math that is within the algorithm. Malware is a kind of technical algorithm in what it does.”

A self-described “machine learning designer/user researcher, artist, and digital anthropologist obsessed with language, culture and images,” Sinders is the founder of Convocation Design + Research, an agency focusing on the intersections of machine learning, user research, designing for public good, and solving difficult communication problems. She has worked with Amnesty International, Intel, IBM Watson, and the Wikimedia Foundation, and her work has been featured in MoMA PS1, the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Slate, Quartz, and other outlets.

A prototype of the “between systems and selves” project was funded by the European Commission’s Joint Research Center, SciArt DataMi program, where she is collaborating with research scientists Henrik Junklewitz and Stephane Chaudron. With funding from the CLTC Arts Contest, Sinders wants “to push these sculptures further by analyzing a series of related viruses and botnet, such as the Mirai virus, and have the sculptures organized into clusters reflecting either strains of a particular virus or botnet.”

Sinders hopes that viewers of the sculptures will “see that very technical systems can be rendered in beautiful, minimal ways. Technical complexity doesn’t always mean aesthetic complexity. Cybersecurity and privacy in general affect everyone. Art can help translate and make certain fields or ideas feel more applicable and real to a general audience. Art can add poetry to space that has felt cold, mechanical, distant or confusing.”

Hack Back Zine: A D.I.Y. Approach to Cybersecurity Education

Joyce Lee

A recent graduate of UC Berkeley’s Master of Information Systems and Management (MIMS) program, Joyce Lee will use funding from the CLTC Cybersecurity Arts Contest to publish a “zine,” an independently produced and distributed magazine, focused on the human impacts of cybersecurity. Tentatively titled “Hack Back” (to “evoke a proactive, yet improvisational ethos with the prankish bent of white-hat hackers,” Lee explains), the zine will will act as an educational resource to facilitate cybersecurity awareness and offer accessible instructions for risk mitigation strategies. The zine will be developed in a workbook format and will be distributed at a range of “do-it-yourself” (D.I.Y.) events across the country.

“The project is intended to foster self-reflection on the reach and impact of cybersecurity practices in daily life,” Lee explains. “Given that it will distributed at events open to the general public, I also hope that it provides a sense of empowerment to those who may be generally concerned with the effects of surveillance and ubiquitous computing but may not necessarily have the technical literacy to identify threats and to implement defensive strategies.”

If traditional paper-based publishing seems like an out-of-date format to build awareness about cybersecurity, that’s part of the point, Lee says. “While paper may seem ill-suited to conveying the risks of digital activities, the medium’s antithetical nature is surprisingly appropriate for imagining alternative realities as well as reshaping security-related decision-making and behaviors,” she explained in her proposal. She also notes that the D.I.Y. spirit of self-publishing aligns with early tech culture, when paper-based publications like The Whole Earth Catalog shaped the ethos of the early internet.

Lee was previously part of a group of collaborators that received a grant from CLTC for a project entitled “Secure Internet of Things for Senior Users.” She has been publishing zines and participating in the zine community since 2015, and she will use her funding to bring her cybersecurity-themed zine to events in Oakland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland, Chicago, Toronto, and New York. She will distribute the publications at events, workshops, libraries, book stores, and other outlets.

Her zine will focus on areas such as cryptography, passwords/account management, and social engineering attacks, but will be “both playful and practical, activating cybersecurity awareness by directly engaging readers in provocative exercises,” Lee explains.

The Price is Wrong

Shayna Robinson and Neema Iyer

Cybersecurity still seems like a foreign topic in Uganda, according to Neema Iyer, Executive Director of Pollicy, a civic technology organization that works at the intersection of data, design, and technology to revolutionize civic engagement and participation. “Major hacks of mobile money and banking system are kept hush and swept under the carpet, with billions lost,” Iyer and her collaborator, Shayna Robinson, wrote in their proposal for a CLTC arts grant. “Conversations on cybersecurity are hidden within small cliques, discussed in complicated English vocabulary, and largely unreachable to a majority of the population.”

Iyer will work with Robinson, a technological artist who creates visual and sonic art electronically, to shift the dialogue around these issues through “Price is Wrong,” a three-part mockumentary series aimed at starting a discussion on cybersecurity within the African context through the lens of comedy and realism. Each 10-minute episode will follow the story of participants who answer questions while riding an Uber in Kampala (in a similar style to Cash Cab). The quiz questions will be aimed at understanding the digital hygiene behaviours of the participants, ultimately testing how much value they place on their personal data and security.

“The aim of the project is to begin a discussion on how we view cybersecurity, personally and in relation to entities,” Iyer explained in an email interview. “There is an urgent need to talk about how technological advancements from abroad — and the laws that are made there — are having immediate and questionable effects thousands of miles away, with little room for a conversation on what role countries in Africa play in this digital avalanche.”

To develop the short films, Robinson and Iyer will conduct research (including interviews and focus groups) to understand the situational context of cybersecurity broadly, then create personas and scenarios to build out different story lines. A car will be decorated with lighting and banners from within, and actors and actresses will play the roles of the car driver (quiz master) and the riders. Scenes will also be shot at venues such as banks, internet cafes, and mobile money kiosks. The videos will be translated into Swahili and French, and will be shared largely over social media channels and in Kibandas (small informal movie halls), as well as at venues like the Design Hub, an open space for artistic events.

“Other than fostering conversation on what cybersecurity means, one of the aims of this project is to use artistry that the audience can feel a connection with,” Iyer says. “A major focus of this project is in using localized characters, language and humor so that the audience feels that this is an important and relevant issue within their current context…. Any opportunity that allows us to work within the intersection of technology and art is a major win. We need more brown/black bodies represented in art, in technology, in what the future looks like, and how we are actually at a focal point where we can change what this future looks like if we act more proactively, rather than reactively, which is the norm in the digital rights community in Africa.”

SweetWire Music Video Cybersecurity Visualization

Greg Niemeyer

Concept SweetWire is a music video project that translates the successful containment of a cybersecurity attack into music and choreographed motion. Structurally, the music video will be conceived as a dialog between hacker and target. The structure casts cybersecurity as “an ongoing dialog arising from the need to balance security and connectivity,” explains the artist Greg Niemeyer, “and as a continuous effort to distinguish legitimate and illicit transactions.”

Niemeyer — whose previous works include Quantopia, the Network Paradox, and Metered Tide — will produce the video in collaboration with Ph.D. students in music at UC Berkeley as well as with Oakland-based music producers from Youth Radio.

As Niemeyer explains, the name of the video refers to fictitious names of hackers and cybersecurity teams, who find themselves in constant dialog. The music video begins with an eight-tone riff progressively matching a target riff of eight tones. As Niemeyer explains, “A rough media sketch of one chord gradually matching a target chord shows how the close coupling of sound and image in this project alludes to synesthesia: what does security sound like?”

Once the two sonic sequences match, the video tracks the various stages of a lateral cyberattack moving through a network, from the installation of a dialer program to more elaborate malware and parallel efforts to contain and thwart the breach. The video ends with a sonification of a reboot from a clean backup, and with a new, but structurally similar eight-tone riff. “It could loop, meaning that cybersecurity is continuous engagement with a wide range of concerns,” Niemeyer says. “The sound and the visuals are closely coupled.”

The video will unite three visual elements: a FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) spectrogram visualisation of the music, LIDAR scans of a dance performance, and LIDAR scans of a corporate building with an executive area, a server room, a shipping room, a production space, a marketing space, and an engineering space.

“The LIDAR approach allows us to show the pointcloud of a body of a dancer moving through pointclouds of walls of the building effortlessly,” Niemeyer says. “When points of the dancer collide with points of the building, the points behave like particles and scatter. The points of the dancer also behave like particles, when they encounter elemental forces, which disintergrate the body pointcloud. These forces, which are generated by a physics engine, represent the defensive resilience of the cybersecurity team, whose role it is to keep the corporation operational.”

The end product, SweetWire, will be a five-minute music video that can easily be distributed online, but also can be presented in gallery, event, or conference settings. In gallery settings, the video will be accompanied by sound-making objects and music stems used in the video, so visitors can play along with the video, emphasizing interaction and dialog.

“The FFT sound visualization acts at times as a forceshield for the body, and at times as a forceshield for the corporation. The video is cut to the beat, showing different moments of penetration and repulsion, aggregation and disintegration. The dancer pointcloud is at times shown moving left to right through the various sections of the building and at times shown moving from the z-depth of the image to the foreground. In the end, the attack is defeated, and the system administrator is better prepared to deal with the next attack, which is looming. Cybersecurity looks more like particle systems than like command prompts, it looks more like a network than a man under a hoodie with glowing green letters. The color palette is restricted to black, white and red to underscore a contemporary dramatic look.”

Tally

Joelle Dietrick and Owen Mundy

Users of the internet are often not aware of how they are continually exposing private information about themselves through cookies and other digital trackers. Artists Joelle Dietrick and Owen Mundy aim to bring attention to that fact through Tally, a free, open-source browser extension that transforms the data that advertisers collect into a multiplayer game.

Once installed, a friendly pink blob named Tally lives in the corner of your screen and warns you when companies translate your human experiences into free behavioral data. When Tally encounters ‘product monsters’ (online trackers and their corresponding product marketing categories), you can capture them in a turn-based battle (‘Pokemon style’), transforming the game into a progressive tracker blocker, where you earn the right to be let alone through this playful experience.

“The internet has grown into a pervasive and automated system dedicated to capturing and selling our attention to the highest bidder,” the artists explain. “Everything we post, watch, or click, is recorded and monetized in order to influence our personality, purchases, and politics. On one hand, these systems provide custom experiences, connect us with millions of people and ideas, and invigorate human culture. Yet, the development of algorithms and intelligent machines to filter, analyze, and exploit our data most often isolates us in bubbles instead of encouraging debate in the public sphere. Rather than promoting peace and equality, corporations develop new technologies to offer distractions and empty truths, use behavioral targeting and automation to influence elections without accountability, and further empower those already in control.”

Dietrick and Mundy have previously collaborated on thought-provoking projects related to data privacy and security, internet health, and justice and equality. One of their best-known works, “I Know Where Your Cat Lives,” visualizes a sample of seven million public photos of cats on a world map, locating them by the latitude and longitude coordinates embedded in their metadata. They also produced Illuminus.io, which depicts a fictional scenario of a corporation deciding your financial services to uncover real-life techniques of data analysis.

The artists have been developing various iterations of Tally since 2014, and the game has evolved as behavior-tracking technologies have become more sophisticated. “As the attention economy has engulfed the entire internet, the concept for Tally has also broadened, to not only all forces of surveillance, but more importantly, to introduce a positive solution that players can work towards in the game,” the artists say. “The experience of playing Tally is intentionally playful and draws on accessible concepts like ‘breaking the internet’, ‘trackers as monster’, and ‘playing with your data.’ We believe these will help ignite a larger ‘viral’ conversation around the issues it addresses.”

Follow the progress on the project’s Github page, or sign up to receive updates at https:///tallygame.net/.

Virtual Caring

Lauren McCarthy, David Leonard

When confronted with the prospect of caring for aging relatives, many Americans are turning to artificial intelligence systems like Alexa and Google Home to fill the need for care and stand in for the presence of family, friends, and medical providers. These systems are meant to provide companionship and physical assistance, as well as constant awareness. But what does this new, intimate link between AI, surveillance, and the aging experience look like? What is the role of AI and remote surveillance in elderly care? And as archives of captured home footage are amassed on servers, how do we become implicated in constructed narratives, either manually or computationally generated?

These questions are at the heart of “Virtual Caring,” a project by Los Angeles-based artists Lauren McCarthy and David Leonard that will be funded in part by a prize awarded through the CLTC Arts Contest. For their project, the artists will install a remotely controlled network of cameras, microphones, lights, locks, and appliances in the homes of volunteer elderly subjects. Then, using the live video to guide them, the artists will serve as virtual caregivers, responding to the residents’ requests – and even proactively making suggestions – while documenting the experience with an array of 360 cameras.

“We are investigating AI’s role as watcher and caregiver for an aging population,” the artists explained in their proposal. “Outsourcing care to AI systems offers convenience, but introduces unforeseen complications. Viewing these systems as utilitarian devices obscures the human responsibilities they carry. Will they be able to serve as advocates for this vulnerable population? Virtual Caring puts the viewer into the role of smart home, giving a direct lens into the ethical dilemmas that are rapidly being codified into artificial intelligence and surveillance systems. This interactive video created from a real-life scenario allows us to confront our relationship with AI partners at the end of life.”

McCarthy has previously performed a similar role as “LAUREN,” a human smart home system; this new work will take the human AI concept to focus on AI in relation to elderly populations. “The aim of this work is to create an immersive 360 VR experience that enables viewers to confront problems of AI, surveillance, automation, data, and privacy, especially in relation to aging,” McCarthy explained in an email interview. “Aging family members is an issue that we [McCarthy and Leonard] have both dealt with in our own lives, and we believe it is one that many people of different ages can relate to. Thinking about smart home technologies in the context of elderly life exposes the questions of privacy, intimacy, and care that are often obscured by advertisements focused on utility and convenience. We aim to open up intergenerational conversations around this topic.”