Throughout 2025, CLTC will be celebrating our 10th anniversary by celebrating some of our successful programs. In this post, we recognize the Cybersecurity Arts Contest, an innovative program that encourages artists working in diverse media to expand public understanding of cybersecurity.

Type the word “cybersecurity” into Google’s image search engine, and the results feature the same tired tropes: glowing blue padlocks, strings of green code, and of course the infamous “hacker in a hoodie,” an ominous figure typing into a computer in a darkened room.

Such depictions may seem harmless, but they can lead to confusion and misunderstanding in the public, as they do not adequately capture the range of threats, bad actors, or human harms of data breaches and cyberattacks. They also can foster a perception of fear and helplessness among internet users, says Nick Merrill, head of CLTC’s Daylight Security Research Lab, a research hub housed in the Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity.

“Such stereotypical depictions limit people’s imaginations about what cybersecurity is, whom it affects, and how accessible it is for them to achieve,” Merrill explains. “With imagery like the hacker in the hoodie, it’s no wonder that most people think cybersecurity is difficult or impossible: how could I ever protect myself against someone like that?”

Since 2019, the Daylight Lab has launched a platform of initiatives designed to push back against public misperceptions about cybersecurity, and to shift how people understand and identify the harms of technology. For example, Merrill led the development of the Cybersecurity Imagery Dataset, an analysis of two years’ worth of Google Image Search results that confirmed that depictions of cybersecurity are highly homogeneous, with a dominant color (cyan blue).

He also developed a card game, Adversarial Personas, to help organizations better understand the kinds of cyber threats they could face, largely by developing “personas” to describe the possible motivations of would-be attackers.

The Daylight Lab’s boldest effort to explore new ways of depicting cybersecurity launched in 2019, with the announcement of the inaugural Cybersecurity Arts Contest. This groundbreaking contest offered funding to artists working in any medium “who create art that expands the world’s understanding of what cybersecurity is or can be.”

An Appeal to Artists: Cybersecurity Arts Contest

The overarching goal of the CLTC Cybersecurity Arts Contest is to expand representations of security beyond tropes like the “hacker in the hoodie,” and to broaden public perception around what security is and who is responsible for it. The contest is aligned with CLTC’s mission to help individuals and organizations address tomorrow’s information security challenges, expand who has access to cybersecurity, and amplify the upside of the digital revolution. It also works in parallel with efforts like the Cybersecurity Visuals Challenge, an initiative developed by the Hewlett Foundation and Ideo that sought to “reimagine the visual language of cybersecurity by elevating more representative imagery.”

“Cybersecurity touches almost everyone,” Merrill explains. “But who feels like they have a meaningful say? Who feels they can get involved? The goal of the Arts Contest is to foster inclusion in security by expanding the way security is represented.”

In its first year, the contest awarded six projects, which were selected based on “their potential to illuminate the human impacts of security and provoke critical dialogue about important issues like privacy, surveillance, cyberattacks, and malware.” The proposals were reviewed by an interdisciplinary committee and judged for artistic merit, relevance, feasibility, and potential impact, including how they might influence other artists or reach particular audiences.

The artists used a wide array of media to bring new perspectives to urgent technology-related topics. For example, as part of a project entitled “between systems and selves,” artist Caroline Sinders used sculpture to depict different types of malware and what operating systems they were designed to attack. Meanwhile, artists Joelle Dietrick and Owen Mundy received a grant to help develop Tally, a free, open-source browser extension that transforms the data that advertisers collect into a multiplayer game.

Some of the projects helped bring a human face to cybersecurity, which is too often regarded as a technical challenge. For a project originally called “Virtual Caring” (later renamed “I.A. Suzie”), artists Lauren McCarthy and David Leonard used a network of cameras and remotely controlled appliances to serve as a “human AI” assistant for the elderly. And for a creative project called “The Price is Wrong,” a team of Uganda-based collaborators Shayna Robinson and Neema Iyer produced a series of “mockumentary” videos highlighting the public’s lack of awareness around cybersecurity.

The Cybersecurity Arts Contest was opened again in 2021, with a new set of artists receiving funding for their innovative work. Among the projects chosen was ONLYBANS, by Lena Chen, which brought to light issues related to digital surveillance and discrimination faced by sex workers, and Resistant Systems, a wellness lifestyle brand featuring “signal-blocking hoodies” that are designed to increase privacy.

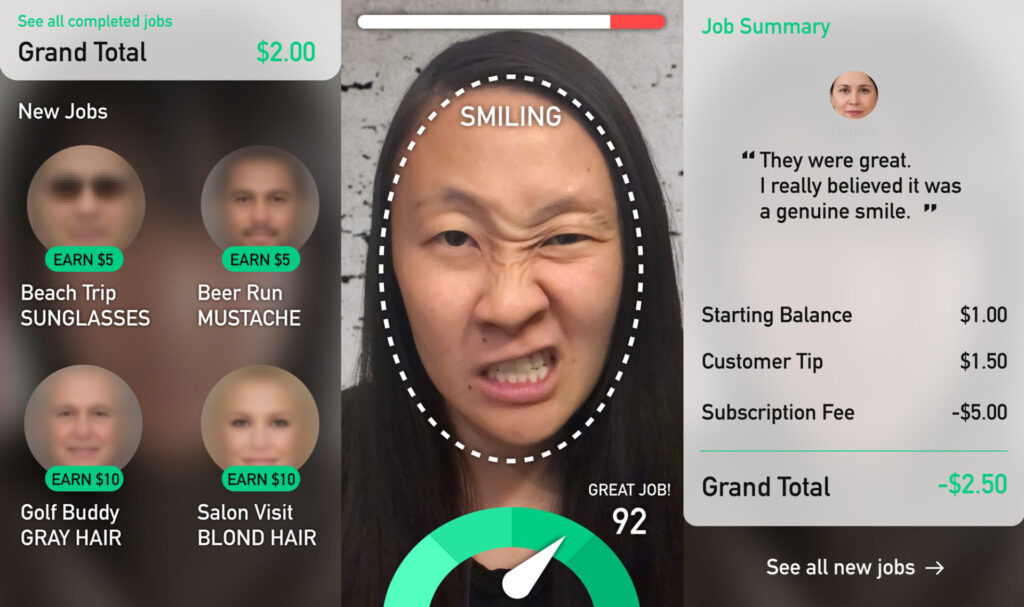

The third Cybersecurity Arts Contest was held in 2023, with three projects selected, including the first prize winner, Facework, by Kyle McDonald, a game that imagines a world where face analysis is key to the latest gig economy app. The game highlights the growing influence of algorithms in our world, and addresses issues of surveillance technology from multiple facets.

In addition to providing funding to contest-winning artists, CLTC organized a series of panel discussions to promote continued dialogue about select artists’ work. These panels helped the artists’ work reach a global audience, and brought together members of the cybersecurity research community with the arts community. The events featured conversations with special guest interlocutors to discuss how new alternatives to contemporary tropes might reshape the way policymakers, technical practitioners, and the general public make decisions about security.

The CLTC Cybersecurity Arts Contest received coverage in popular security publications like Dark Reading. “Powerful art can cause upset as easily as it can soothe,” wrote author Terry Sweeney. “At its most effective and high functioning, art fosters conversation and changes the ways we think about challenging topics — like cybersecurity. That, in a nutshell, is the driving force behind [the CLTC Cybersecurity Arts Contest].”

Read below for more information about the CLTC Cybersecurity Arts Contest Winners

2019 Cybersecurity Arts Contest Winners

“between systems and selves,” Caroline Sinders

Inspired by the work of Alexander Calder and Giorgia Lupi, Caroline Sinders developed a series of “poetic sculptures” based on malware, or malicious software. The series featured 100 to 1,000 sculptures made out of thin wood and metal, each designed based on parameters of different types of malware, such as what operating system the malware is designed to attack.

“(In)visible,” Joyce Lee

Artist Joyce Lee publish a “zine,” an independently produced and distributed magazine, focused on the human impacts of cybersecurity. The publication, “(In)visible,” was designed to serve as an educational resource to facilitate cybersecurity awareness and to offer accessible instructions for risk mitigation strategies. The zine was developed in a workbook format and distributed at “D.I.Y” events across the country. Read an interview with Joyce Lee.

“The Price is Wrong,” Shayna Robinson, Neema Iyer

Uganda-based artist Shayna Robinson and Neema Iyer, Executive Director of Pollicy, produced “The Price is Wrong,” a three-part mockumentary series intended to start a discussion on cybersecurity within the African context through a lens of comedy and realism. Each 10-minute episode follows the story of participants who answer questions while riding an Uber in Kampala (in a similar style to “Cash Cab”). The quiz questions are aimed at understanding the digital hygiene behaviors of the participants, ultimately testing how much value they place on their personal data and security. Watch a conversation with the artists.

“SweetWire Music Video Cybersecurity Visualization,” Greg Niemeyer

SweetWire is a music video project that translates a successful containment of a cybersecurity attack into music and choreographed motion. Structurally, the music video is a dialog between hacker and target. This approach casts cybersecurity as an ongoing dialog arising from the need to balance security and connectivity, and as a continuous effort to distinguish legitimate and illicit transactions. Watch a panel discussion with the artists.

“Tally,” Joelle Dietrick and Owen Mundy

Internet users are often not aware they are continually exposing private information about themselves through cookies and other digital trackers. Artists Joelle Dietrick and Owen Mundy aimed to bring attention to that fact through Tally, a free, open-source browser extension that transforms the data that advertisers collect into a multiplayer game. Once installed, a friendly pink blob named Tally lives in the corner of your screen and warns you when companies translate your human experiences into free behavioral data.

“Virtual Caring,” Lauren McCarthy and David Leonard

Many Americans are turning to artificial intelligence systems like Alexa and Google Home to fill the need for care of elderly relatives. “Virtual Caring,” by Los Angeles-based artists Lauren McCarthy and David Leonard, explored the links between elder care, AI, and surveillance. The artists installed a remotely controlled network of cameras, microphones, lights, locks, and appliances in the homes of elderly subjects. They then served as virtual caregivers, responding to the residents’ requests — and even proactively making suggestions — while documenting the experience with an array of 360-degree cameras. Watch a conversation with the artists.

2021 Cybersecurity Arts Contest

“Community Emotional Light Sound Organism,” by Driven Arts Collective

Biosensing technologies are increasingly used by neuromarketers, governments, and security contractors to make normative judgments about people’s physical fitness and mental health through the categorization of physiological data into emotional schema — often without respect for the privacy and agency of the individuals and communities whose lives are surveilled, analyzed, and judged through these biosensing technologies. To explore these themes, Driven Arts Collective, a group of San Francisco Bay Area-based artists, dancers, musicians, and engineers, presented “Community Emotional Light Sound Organism,” or CELSO, in which dancers wore biosensing masks and transmitted their emotional data during live performances. CELSO sought to raise awareness about the use of emotional data surveillance in public, and the potential cybersecurity risks for people who are miscategorized or othered.

ONLYBANS, by Lena Chen

The internet has long been celebrated as a limitless realm of free expression, but this digital wonderland is becoming increasingly oppressive to those who express their sexuality as part of their art or work. Created by sex workers and allies, OnlyBans is an interactive game that critically examines the policing of marginalized bodies and sexual labor to empathetically teach people about digital surveillance and discrimination faced by sex workers. Assuming the role of a sex worker, players attempt to establish an online fanbase and earn money through posting sexy images. Players encounter content moderation algorithms, shadow-banning, “real name” policies, facial recognition software, and other threats based on actual experiences of sex workers. As the player attempts to evade being censored by Instagram, flagged by Paypal, and watched by Microsoft, the game reveals just how “free” the internet really is when you are engaged in stigmatized labor subject to policing and criminalization.

“Cyber Cipher: Training Black Cybersecurity Psychosocial Designers,” by Alan Waxman, Tameel Marshall, and Callie Wheeler

As companies and nation-states increasingly rank and privilege their employees or citizens based on their behavior, certain locations and groups become marginalized and stigmatized. This project addressed the tension between social credit rating systems and software-as-a-service resulting in inherent AI-based discrimination. The project was led by a team of three artists affiliated with an initiative called AWED – Alan Waxman Social Design: Alan Waxman, a PhD student in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at UC Berkeley; Tameel Marshall, a poet and chef in Brooklyn who curates psychological environments through music, word, and fashion; and Callie Wheeler, a user experience-centered product manager who focuses on social and interactive experiences.

“Resistant Systems,” by Tim Schwartz

Founded by artist Tim Schwartz, Resistant Systems is a digital-focused wellness lifestyle brand that includes organic, hand-woven signal-blocking hoodies for dropping off the grid, patterns for hand-stitched scarves that obfuscate facial detection, cleansing kits for passwords and social media, encrypted USB necklaces housed in shungite crystals, and hand-created operating systems ready to rebirth desktops into anonymous research stations. The project also includes the Manual of Digital Resistance, which describes safe ways to gather information, secure, and communicate sensitive information.

“The Future of Memory,” Qianqian Ye and Xiaowei Wang

In the era of AI, automated censors can dictate what gets remembered — and what gets forgotten. How can internet users reclaim agency? This is the central idea behind The Future of Memory, by artists Qianqian Ye and Xiaowei Wang, a series of browser-based games, playful and artistic tools, and public workshops that teach internet users how to outsmart censors and build “machine resistant” communications. The Future of Memory exams the fact that language online has become the medium in which expression and activism arise in the US, in China, and globally. The goal of the project is to help people understand the current state of automated censorship and come up with creative ways to bypass the systems like OCR (optical character recognition). The artists also used the tools in their previous work, the Algorithmic Censorship Resistance Toolkit, a compilation of different tactics that obfuscate and encode text so that it becomes machine unreadable.

2023 Arts Contest

Facework, by Kyle McDonald

Kyle McDonald’s Facework is a game that imagines a world where face analysis is key to the latest gig economy app. As a Faceworker, the player is required to “audition” for each new job. The game begins with innocuous challenges, such as to smile or wear glasses. But as they choose their path, an unexpected interruption takes the game in a new direction, accompanied by increasingly uncomfortable criteria for job suitability. Facework addresses issues of surveillance technology from multiple facets, including the collection of personal and intimate data by corporations and institutions, but also the ways in which we freely share such information through our recreational use of social media or online games.

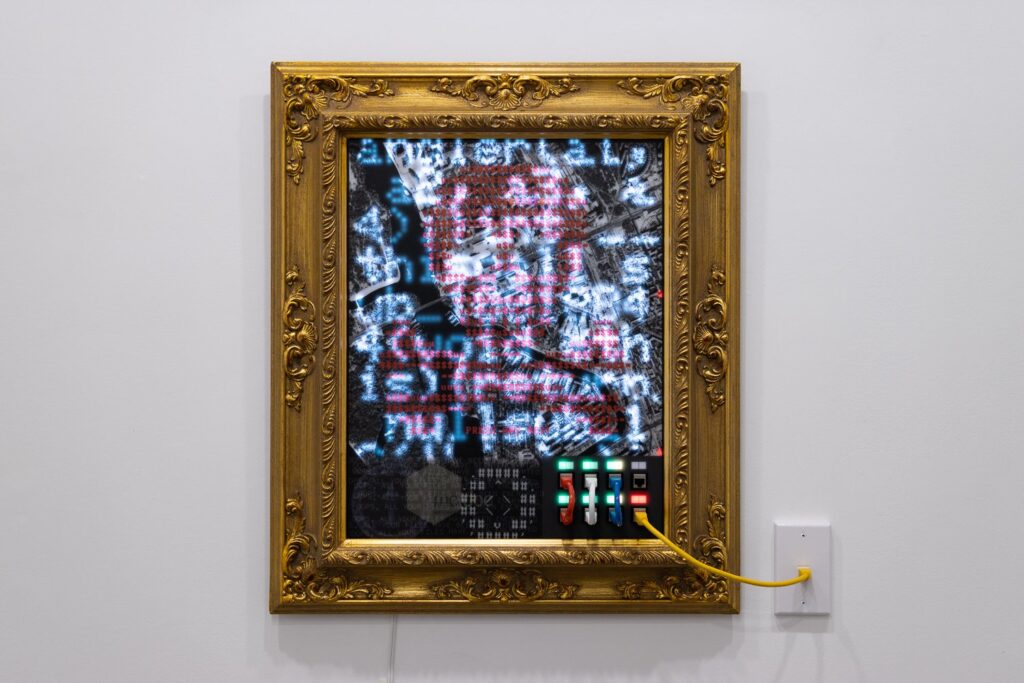

Portrait of a Digital Weapon, by Mac Pierce

Issues of cybersecurity are rarely couched in terms of warfare to the larger public, and are often portrayed as one-off attacks or the work of stateless cyber criminals. Mac Pierce’s Portrait of a Digital Weapon is a series of electronically activated portraits depicting infamous, real-life examples of computer viruses, such as Stuxnet and NotPetya, being used as a tool of geopolitical and financial attack by nation-states. Each piece reads off the decompiled source code of the virus while displaying select elements of how each of the viruses operated and satellite imagery of the attack target. The ongoing Portrait of a Digital Weapon series attempts to bring these covert attacks to light and highlight these viruses for what they are — cyber weapons.

Kristine is Not Well, by Seeyam

Seeyam’s Kristine Is Not Well is an animated social media simulation that visualizes how internet users protest against algorithmic surveillance and censorship with interactive and spatial metaphors in virtual reality (VR). Based on real online protests and existing anti-censorship practices used by online activists, the project uses immersive technology to allow users to more deeply connect and experience the dimensionality of geopolitical social movements. Kristine Is Not Well begs the question of how we define cybersecurity in a quickly evolving digital age, and how the amplification of one’s voice and social issues can be protected within dynamic online spaces and technologies.