The Clock is Ticking for Companies to Improve their Data Breach Notification Practices

By Allison Davenport

On May 25, 2018, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will come into effect following a two-year implementation period. The GDPR is one of the most comprehensive privacy laws ever passed and affects any company that handles the data of European citizens. This unprecedented regulatory framework creates new rules about consent, data management, and storage, and extends “the right to be forgotten” beyond individual countries’ jurisdictions.

Among the regulations outlined in the GDPR, the data breach notification requirement is likely to be particularly problematic for American companies. The United States currently has an array of state privacy laws that require companies to notify consumers about a data breach, but the time requirement ranges from “without unreasonable delay” to a deadline of 45 days. Article 33 of the GDPR sets the deadline for data breach notification at 72 hours, and any delay beyond that must be accompanied by an explanation. Companies that fail to comply with this requirement face potentially massive fines: up to 4% of annual revenues or 20 million Euros.

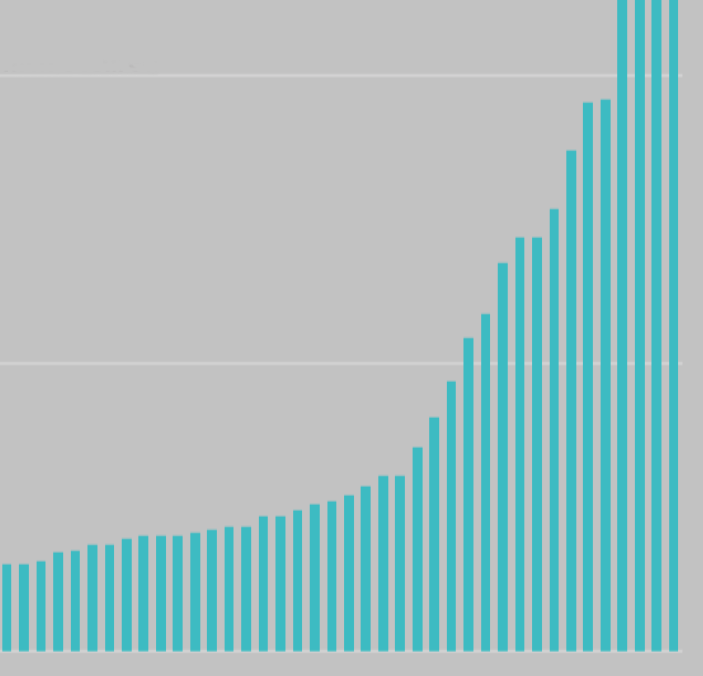

But how big of a change is the GDPR’s 72-hour deadline in reality? The UC Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity looked at data from the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, a website that catalogs data breach incidents, and extracted nearly 80 publicly recorded data breach incidents from the last 10 years. We then compared the reported discovery date with the date on which the breach was made public to compile a sample of existing practice.

While our research does not take into account private notifications that companies may have made to data protection authorities prior to public announcement, in several high-profile cases, public notification and formal government notification occurred around the same time. For example, in October 2016, Uber paid hackers $100,000 to delete data they had stolen about 57 million customers and drivers, yet the company did not reveal the breach to the public or any regulatory authorities until November 2017. Additionally, in January 2017, the SEC launched an investigation into whether Yahoo had violated laws by waiting more than two years to report a 2014 data breach.

Our sample indicates that most companies fall far short of the GDPR’s requirements in their standard notification practice. Companies complied with the GDPR’s 72-hour requirement in only 9.1% of the breach incidents we analyzed. Around two thirds (67.5%) provided notification within deadlines set by state privacy laws, but the leap from 45 days to 72 hours is significant, and the broad application of the GDPR sets a de facto standard for data breach reporting that companies will be hard-pressed to meet.

Consensus has not yet been reached on the efficacy and timing of data breach notification, which remains a complicated subject. A 2016 RAND survey found that a majority of consumers valued prompt notification of a data breach and continued to do business with the breached company. However, the researchers were not able to determine whether the customer loyalty was due to the company’s breach notification practices or whether customers were simply “trapped” due to the difficulty and cost of moving their business elsewhere. Critics of data breach notification laws argue that rushing data breaches may cause companies to release information before they have fully assessed a breach, may create unreasonable burdens on small businesses, or may even create a roadmap for cybercriminals. It is possible that the hard deadline and significant penalties of the GDPR may effectively shut down any nuanced debate about data breach notifications, leaving companies to focus on what they must do rather than what they should.

The GDPR was adopted on April 17, 2016, and companies were given a two-year window to bring their practices into compliance. The clock is ticking toward the May 25 deadline, and if our research is any indication, many American companies still have a lot of work to do to comply with Europe’s new privacy law.

Allison Davenport is a former researcher at the UC Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity.